|

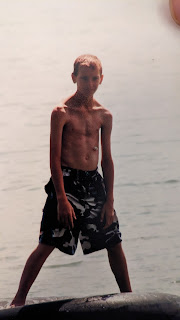

| One of the last pictures I could find before I got my feeding tube, circa 2004 |

About 18 years ago, I was in first grade. I was pretty much like any first grader; I enjoyed learning, my favorite sport was baseball, I spent a lot of time outside playing games and using my imagination. I liked superheroes, I had a lot of friends, I was curious. And I had a feeding tube.

|

| One of the first pictures I have of me with my tube, circa 2005 |

Getting my feeding tube was one of the first surgeries I ever had. If I’m being honest, I can’t really recall the emotions I felt as a first grader who learned they had to get a tube placed in their stomach. I wish I could say for certain that I was nervous or scared, but honestly, I don’t know if I even really knew what it was or what it meant. I suppose, in a way, I was fortunate not to realize that. Ignorance, in this case, was bliss. If the doctors or my parents would have told me that for the next 18 years of my life, I’d have this… thing sticking out of my stomach, I probably would have been pretty adverse to it.

Like most kids who need surgery in first grade, sure I was probably scared and nervous. But I had a wonderful support system and I got the tube placed. In fact, I actually got to show it off for show and tell later in the year! (Thanks, Mrs. Birch, for humoring 7-year-old me.)

Now, at 25, it is hard to remember life without a feeding tube. 18 years is a long time, especially when that clock starts when you’re just 7 years old. I was too young to realize the magnitude of the surgery. Before that milestone in my life, I hadn’t really “needed” a flat stomach, if that makes sense. Except for the occasional slip and slide, I wasn’t diving headfirst into anything, I wasn’t thinking about what kind of contact sports I might want to play. I didn’t go off diving boards or ride waves in the ocean with a boogie board. I didn’t slide across ice or snow like a penguin. Because I was young. Those things hardly even crossed my mind, ever.

But now, those things can cross my mind without being immediately dismissed. Not that I have a lot of opportunities to go on slip and slides, or dive headfirst into a base or off a diving board, or play contact sports or anything like that. But that’s not the point; the point is that now, I can do those things.

Because after 18 years of having a feeding tube, I was recently able to remove it, for good.

My feeding tube has simply served its purpose. When it was placed 18 years ago, I was severely underweight, just as many CFers are. It enabled me to receive extra nutrition and calories when I slept overnight. I’d hook up my feeding tube to a machine that essentially fed me throughout the night, pumping me with something like an additional 1,000 - 2,000 calories while I slept. I didn’t have visions of sugar plums - I had visions of turkey feasts.

The last time I remember using my feeding tube was right around April 2020, nearly three years ago. I actually think I might have used it once or twice between August and September of 2020, but even so, it's been a while. And, in fact, before April 2020, I rarely used my feeding tube. In college, my use was so sporadic, I’m sure it did help, but not to the extent it could have.

Once again, thanks to a combination of my own motivation and dedication to my health, along with the miracle drug Trikafta, I have been able to shed more burdens and aspects of CF that have been so extremely foundational and instrumental in my life, for as long as I can remember.

It is so strange to have this part of me now removed. I am flooded with emotions: excitement, relief, freedom, grief. I don’t remember life without a feeding tube. I have grown so accustomed to having it in. My body naturally protects my stomach when I am in crowds or close to bumping into a wall. My hands reach for the area after I jump in the water or take off a sweater. I can already feel the “phantom limb” taking effect; my mind and body expect the tube to be there, and I still am surprised when it’s not.

Right now, I’m keeping some gauze over the site. When I took it out, there was no procedure, no stitching; my doctor said it should heal on its own and close up. So really, there’s just been a hole in my stomach for the last week, which has been kind of freaky. After I eat a meal, the site will sometimes leak a bit, but even that has reduced significantly. What’s going to be really weird is when I can take off the gauze and just have a plain, flat stomach.

Other CFers have reported having their site heal up but leaving a deep scar — they’ve described it as basically having a second belly button. So the staring might not stop, but after 18 years, I’m used to it. What I do need to get used to is the freedom I’ll have. This summer, I definitely want to go on what I can only imagine is one of my first head-first dives into a slip and slide. I want to play baseball and steal second, sliding into the base with my arms outstretched. I want to play frisbee and layout for the disc. Maybe I’ll even try my hand at tackle football (probably not, but it won’t be because of my feeding tube!).

My feeding tube and I have been through some stuff. There are at least 4 separate occasions that I can recall it falling out suddenly and me needing to quickly get it replaced, including once in the ocean and once at the local pool. Life is always exciting.

It’s going to take me some time to get used to this new body, for sure. My feeding tube has become such a familiar site and feeling for me. I am shedding a part of my life that I literally do not remember not having. But this is going to open up more opportunities for me, as well. And, just like everything else, it signifies the progress we are making toward a cure for CF.